- Home

- Managed Services

- Cyber Security

- Blog

- About Us

We, Global Cyber Tech, simplify your IT problems

Call for a free support. +1 -8273-456-478Platform Partnership

- Pages

- Who We Help

- Shop

- Contact Us

The Issues Impacting Digital Forensics In The Cloud

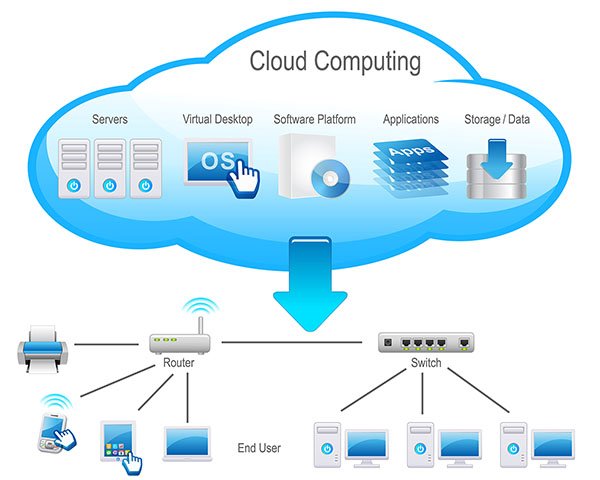

Cloud Computing Overview

Cloud computing is a model for enabling convenient, on-demand network access to a multi-tenant pool of configurable computing resources. These resources may consist of networks, servers, storage, applications and services. The resources should be able to be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal Cloud Service Provider (CSP) interaction, based upon demand, which is a concept known as rapid elasticity. However, the CSP may control and optimize resources in accordance with the contracted upon levels of service, which typically are on a pay-per-use basis.

Furthermore, in terms of geo-location of the cloud, the entity typically has no control or knowledge of the exact location of the provided resources, though they may be able to choose a general location such as country, state so as to reduce network latency. The CSP must also provide network access to a broad and heterogeneous array of thin or thick clients such as mobile phones, tablets, laptops, and workstations (Mell & Grance, 2011).

Service Models

Cloud computing providers typically offer their services in one of three ways. The first of the core model types is Infrastructure as a service (IaaS) where the entity outsources its’ operational equipment such as storage, hardware, servers and networking components. In this model the CSP retains ownership of those resources, and the entity will typically pay on a per-use basis. Platform as a service (PaaS) contrasts with IaaS, in that infrastructure resources are sold in conjunction with hosted software applications that the entity may use to develop business solutions. While the afore-mentioned may seem quite similar to Software as a service (SaaS), the distinction is that the CSP provides pre-configured applications to the entity, such as billing systems, project management, ERP, CRM solutions, et cetera.

In Monitoring as a Service (MaaS), the CSP provides business state monitoring capabilities, such as instantaneous violation detection, and system performance monitoring (Meng & Liu, 2012). In the closely related Forensics as a Service (FaaS), we find that security as a service is being introduced to the cloud. With it, companies are delivering anti-virus solutions, and making use of the massive computing power of the cloud for forensic analysis. Indeed, one major CSP, Terremark, offers forensic-as-a-service (Terremark, 2013). However, potential downsides to a forensic support service may be response time, which may be predicated on the Service Level Agreement (SLA) and the providers’ lack of knowledge on how the entity is using the cloud to meet its’ business goals (Dykstra & Sherman, 2012).

And finally, there is the catch-all X as a Service (XaaS), which encompasses the above-mentioned (Lineage, 2011); as well as Communication as a Service (CaaS) which entails enterprise level communications solutions such as VoIP, IM, collaboration and videoconference applications. There is also DaaS (Data or Database or Desktop as a Service); in the latter the CSP provisions a virtual desktop to a user, wherever the user has Internet connectivity (Schaffer, 2009).

Deployment Models

There are four primary means by which the cloud may be deployed, the first is the Private Cloud which makes use of non-shared resources, as the infrastructure is operated solely for a specific entity. In this model the cloud may be on or off-site, and may be managed by the entity or a CSP. Conversely, a Public Cloud is offered by the CSP to the general public, and as such it shares its’ resources. Similarly, in a Community Cloud multiple entities will share the clouds’ resources, however these entities will have a concern in common, such as their mission, compliance constraints, or other criteria. Finally, as the name connotes, a Hybrid Cloud is an amalgam of two or more deployment models that remain distinct entities but that are bound together by standardized or proprietary technology which enables data and application portability.

Cloud Virtualization Methods

Virtual Private Server (VPS)

Most CSPs implement redundancy by the use of virtualization that is monitored and provisioned by a hypervisor, or virtual machine manager. The hypervisor in a cloud may be likened to the traditional operating system kernel, as such the hypervisor may be prone to malicious attacks (Ruan et al., 2011).

Due to user and vendor ambiguity about the definition of “the cloud”, we may see some CSPs offering VPS for cloud deployment. A VPS is a single dedicated server that has been partitioned so that each partition may appear as a virtual server operating in a multi-tenant hypervisor environment.

In this model, each VPS will utilize its’ own finite disk space, bandwidth, and operating system. As the resources of the VPS are finite, this breaks one of the key tenets of the definition of the cloud, that the resources must be scalable upon demand. Nonetheless, if our forensic analysis is to be conducted on a VPS generated cloud; this may impact the techniques and methodologies we will employ.

Nested virtualization

In standard virtualization, we use the physical machine as the host hypervisor to install virtual machines termed “guests”. In nested virtualization, we find that the hypervisor is also a guest running inside a virtual environment, and that it too can host virtual machines. Nested virtualization has many uses, such as architectural research, security, and cloud implementation. As an example, an IaaS provider could give a user the ability to run a user-controlled hypervisor as a virtual machine, which would allow the user to manage their virtual machines directly with their desired hypervisor (Ben-Yehuda, 2010). Therefore, nested virtualization not only supports the ability to virtualize a hypervisor on top of another hypervisor (Jones, 2012), but it may also present a challenge to forensic analysts when they must deduce the true and accurate specifications of the suspect system.

Technical Issues of Cloud Forensic Investigations

Proprietary Technology

A forensic investigation may be impeded by the wide diversity of technologies deployed by the CSP. Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2), and CSP Rackspace for example, utilize Xen virtualization, whereas CSPs EMC2,, Verizon Terremark vCloud Express, and VMware utilize the proprietary VMWare vSphere technology. Another major CPS, Microsoft Azure uses a specialized operating system, Windows Azure and a customized version of Hyper-V, known as the Windows Azure Hypervisor to provide virtualization of services.

Security Policy

Outsourcing sensitive corporate data into the cloud raises concerns regarding the privacy and security of data. To meet these concerns, the entity must modify their traditional security policy to fit the demands of the cloud. There should be a listing of approved devices, and end-users should be trained in the proper usage of cloud technology. Furthermore, there should be joint security planning throughout the organization, as cloud computing is not an independent technology, indeed it relies on multiple intertwined infrastructure components to function. Therefore, there are many attack vectors for forensic and security personnel to consider when responding to an incident, or in preparation for one.

Cloud Exploits

There are a fair number of exploits that may be perpetuated against the cloud. One is the unauthorized access to the user management interface of the entity; due to the on-demand self-service nature of the cloud that requires a user interface. Related to this exploit, are Internet protocol vulnerabilities as a result of the ubiquitous network and device access that may occur via standard protocols. As we are aware, most cloud access occurs through the Internet, which must be considered untrusted, therefore Internet protocol vulnerabilities that allow MitM attacks and other exploits are applicable to cloud computing.

Identity management, authentication, authorization, auditing (IAAA). Many CSPs apply two-factor authentication, and IAAA issues are not just cloud specific, however in cloud authentication there are often weak credential-reset mechanisms.When CSPs manage user credentials themselves rather than using federated authentication, they must provide a mechanism for resetting credentials in the case of forgotten or lost credentials. Currently of all the IAAA vulnerabilities, authentication issues are the primary vulnerability that puts user data in cloud services at risk (Grobauer, Walloschek & Stocker, 2011), which is a challenge for IA and forensic personnel alike.

Fast-flux networks. In our work with the Amazon EC2 platform, we have taken note of the relative ease to rapidly provision a service. As such, a fast-flux network is a FQDN such as www.spamalot.com, which will have hundreds, or thousands of IP addresses assigned to it. IP addresses are rotated in and out of flux, as rapidly as every 3 to 10 minutes. While the pool of Amazon EC2 IPs is fairly large, it is finite and also traceable, which has led to some of the IPs being blacklisted for use with email clients. Typically, the IPs in fast-flux exploits are those of compromised home computers of average citizen, however now cyber-criminals may opt to utilize a cloud VPS set up for this exploit.

Cloud Network Forensics

Cloud Forensic Techniques

Cloud forensics may be deemed a subset of network forensic due to the shared collection of configurable networks, servers, storage, applications and services that the cloud makes use of. (Ruan et al., 2011) Therefore, one fundamental network forensic technique that we may employ for our investigation is the use of the limited machine image at hand rather than a full machine image, though this will preclude access to items in RAM or in other components that might fall into the standard forensics review (Lillard, 2010).

An additional consideration of cloud imaging is the probable enormity of the data with-in the cloud, due to the clouds’ elastic ability to dynamically scale its’ storage capacity. This may prove problematic, as the sheer volume of physical media in a cloud may render imaging impractical, and partial imaging can face legal challenges (Grispos, Storer & Glisson, 2011). One potential solution to this is the implementation of another cloud to store our forensic data. And at the risk of being remiss in stating this central tenet of digital evidence obtainment, whatever methodology is employed for image collection, it is imperative that we subject our results to hashing for integrity checking purposes.

Ideally, we will attempt to gain physical access to the VM that is deploying the cloud, and make use of forensic tools to access the memory of the guest VM. There are two ways to accomplish this: modifying existing forensic software to extend its capabilities and presenting the memory of a guest VM in a format that forensic memory analysis (FMA) tools can understand. The former would allow FMA software to take advantage of the live nature of VM analysis; however, the latter requires no modifications to existing tools.

Researchers (Dolan-Gavitt, Payne, & Lee, 2011) have implemented two procedures to permit existing applications to interface with the memory of a guest virtual machine as a file system interface and an extension API. The file system interface exposes guest memory as a regular file on the host, allowing FMA tools that process memory dumps to operate on guest memory with no modifications. The extension API would necessitate a small number of modifications to the forensic software to permit access to guest memory using an analysis library such as XenAccess. Although the file system interface is more general, the extension API can provide a forensic tool with additional information that may improve its analysis capabilities. Both interfaces have been freely released as part of XenAccess, thus they may benefit other researchers.

If it is not possible for an investigator to access the cloud service, it may be possible to obtain an image of the services’ data from the CSP, though this approach is problematic for a number of reasons. One key concern is that the veracity of the chain of custody may be questionable, as the investigator has not had sole and primary custody of the evidence.

Another consideration that may impact the admissibility of the cloud forensic evidence obtained from the CSP is whether the personnel that acquired the evidence were competent to do so, and did they do so in a lawful and standards based manner. Furthermore, the cross-organizational nature of this approach to evidence gathering from cloud environments has other implications. As previously discussed, the use of proprietary technologies by cloud providers may render the involvement of the provider in the investigation essential (Grispos, Storer & Glisson, 2011).

In acquiring cloud data we must also be mindful of the configuration of the cloud firewall and other ingress and egress points. Vendors such as Amazon permit end-users to configure their networks to allow or deny traffic, and in many instances ports must be opened to allow the agents to communicate with the command and control node. Then too the investigators must consider the costs associated with a remote forensic investigation. While not cost-prohibitive, imaging and retrieving a virtual hard drive and its associated memory may incur significant bandwidth costs. To again site the CSP Amazon as an example, based upon outbound data transfer expense of $0.150 per GB, the retrieval cost of 1TB of data would be $150.

Browser forensics. The web browser on the client system is typically the sole user agent that the end-user utilizes to communicate with the service in the cloud. As we conduct our forensic analysis we should take note of searches performed, websites visited, files downloaded, information entered in forms, web-based email contents, persistent browser cookies, and Browser Helper Objects (BHOs) that may have been used for malicious purposes.

Honeynets. Another network forensic analysis technique that we may utilize is the use of a virtual honeynet. These honeynets may be used to simulate the TCP/IP stack of actual cloud systems, with the accompanying network, replete with a simulated routing topology and configurable link characteristics such as delay, bandwidth, packet loss et cetera. As such, the honeynet may be used to attract malicious traffic and glean data on the incident (Meghanathan, Allam & Moore, 2009).

Legal Challenges of Cloud Forensic Investigations

Evidence Presentation

As cloud technology is still in somewhat of an embryonic state, there is a huge lack of standards, policies, procedures and techniques for law enforcement and cloud investigators to draw on when conducting their forensic investigations. However, we can with confidence state that cloud forensic evidence will be subject to the standards of (Daubert, 1993), and quite likely Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence, and possibly international rules of evidence, given the cross-jurisdictional nature of the cloud.

Nonetheless, there are still evidentiary hurdles, particularly when it comes to cloud data, such as those pertaining to authenticity and hearsay. When presenting an e-mail, blog post, instant message or other communication that resides solely in the cloud, there may be a need to secure declarations, deposition testimony, or even live testimony of the author(s), the recipient(s), the data custodian, and/or the CSP (Forsheit, 2009).

In support of this, the U.S. Supreme Court in Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts(2008/2009) found that notarized forensic analysts’ reports without live testimony violate the Sixth Amendment right to confront a witness under the Confrontation Clause and are therefore precluded from evidence. The finding in Melendez-Diaz affects all forms of forensic evidence including cloud digital forensics. As a result, in order for forensic evidence to be considered by a jury, at least one directly involved analyst must deliver live testimony without deviation from the expert report (Lillard, 2010).

Digital Provenance

Digital provenance is meta-data that describes the history of a digital object, and that can attest to the chain of custody and workflows that were used to derive the product from the source. As cloud data may be physically stored in one or more geographically distributed locations, determining the applicable legal framework and procedures to apply to the evidence gathering process may be problematic due to cross-jurisdictional standards. A local search warrant to search and seize evidence may not give the investigator the right to do the same with evidence located in different jurisdictions, even though the evidence is accessible via the Internet (Wang, 2010) Therefore geo-location is a major factor in cloud forensic investigations, as an example, Amazon stores European Union customer cloud data from customers in the Republic of Ireland (Wauters, 2008) Therefore, an investigator seeking evidence on an E.U. user would need to comply with the legal requirements of that jurisdiction, which could be time-intensive while procuring the requisite permissions, and evidence could be lost or deliberately destroyed in the interim.

Regulatory Compliance

Business entities often must comply with a myriad of regulatory constraints. For health-care providers there is HIPAA, and for financial institutions there is Sarbanes- Oxley (SOX). For federal agencies, and their contractors there is FISMA. For FISMA cloud compliance, the NIST Computer Security Division has proposed the following nine-step process for increasing the security of federal agency IT systems: Categorize information and information systems, and select the appropriate minimum or baseline security controls. Refine the security controls using a risk assessment and document the security controls in the system security plan. Implement the security controls in the information system and assess the effectiveness of the security controls. Determine agency-level risk to the mission of business case, authorize the information system for processing, and monitor the security controls on a continuous basis (Toomer, 2011).

Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). Businesses that work with credit card information must comply with PCI DSS directives, and compliance issues may become exacerbated in multi-tenant cloud environments for PCI members. One key PCI DSS requirement is the strict detachment between the systems processing credit card data and other systems, to prevent functions with different security levels from co-existing on the same server. This requirement had caused a bit of confusion for PCI member security personnel, as to what constituted a “cloud component”. However, v2.0 of the PCI standard has provided a degree of clarification, and defined system components as any virtualization components such as virtual machines, virtual switches/routers, virtual appliances, virtual applications/desktops, and hypervisors (“PCI Security Standards Council”, 2013).

As regards digital forensic analysis, the PCI council mandates that logs in all cloud environments provide thorough tracking, alerting, and analysis in the event of an incident. This is very helpful, for as we are aware, in a forensic investigation determining the cause of a compromise is very difficult without system activity logs. Nevertheless, the customer may only be able to access a limited amount of evidential data and most likely will still have missing observations in the forensic time-series of the investigation. Therefore, complying with PCI DSS directives may prove difficult in a public cloud investigation, as CSPs often provider generic or no audit reports (Birk & Wegener, 2011).

Conclusion

For cloud forensics there is no one-size fits all approach when conducting an analysis. There are many technologies, methodologies, laws and regulations that must be considered and weighed when one is performing a forensic analysis. As we begin our analysis we must consider and factor in which of the many service models are being implemented, as well as which type of deployment model. We must also be cognizant that there is more than one type of cloud virtualization method. As analysts we must be particularly mindful of the wide array of presently existing cloud vulnerabilities and those that loom on the horizon. Finally, as technology in general, and virtualization and cloud technology specifically are evolving at a lightning like rate, the field of cloud forensic analysis will continue to be a challenging, albeit rewarding one.

References

Ben-Yehuda, M., Day, M. D., Dubitzky, Z., Factor, M., Har’El, N., Gordon, A., … & Yassour, B A. (2010, October). The Turtles project: Design and implementation of nested virtualization. In Proceedings of the 9th USENIX conference on Operating systems design and implementation (pp. 1-6). USENIX Association.

Biggs, S., & Vidalis, S. (2009, November). Cloud computing: The impact on digital forensic investigations. In Internet Technology and Secured Transactions, 2009. ICITST 2009. International Conference for (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Birk, D., & Wegener, C. (2011), Technical Issues of Forensic Investigations in Cloud Computing Environments. Retrieved from http://code-foundation.de/stuff/2011-birk-cloud- forensics.pdf

Cisco. (2012). Transitioning to the Private Cloud with Confidence. Retrieved from http://www.cisco.com/web/learning/le21/le34/downloads/689/rsa/Cisco_transitioning_to _the_private_cloud_with_confidence.pdf

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

Digital investigations in the Cloud. (2011). QCC Information Security Ltd. Retrieved from http://qccis.com/docs/publications/WP-Digital-Investigations-in-the-Cloud.pdf

Dolan-Gavitt, B., Payne, B., & Lee, W. (2011). Leveraging forensic tools for virtual machine introspection. Retrieved from https://smartech.gatech.edu/bitstream/handle/1853/38424/GT-CS-11-05.pdf?sequence=1

Dykstra, J., & Sherman, A. T. (2012). Acquiring forensic evidence from infrastructure-as-a -service cloud computing: Exploring and evaluating tools, trust, and techniques. Digital Investigation, 9, S90-S98.

Forsheit, T. (2009). Legal implications of cloud computing, Part 4: E-discovery and

digital evidence. Information Law Group. Retrieved from http://www.infolawgroup.com/2009/11/articles/cloud-computing-1/legal-implications-of– cloud-computing-part-four-ediscovery-and-digital-evidence/ Grispos, G., Storer, T., & Glisson, W. B. (2011). Calm Before the Storm: The Challenges of Cloud Computing in Digital Forensics. Retrieved from http://www.dcs.gla.ac.uk/~tws/papers/grispos11calm -rev2425.pdf

Grobauer, B., Walloschek, T., & Stocker, E. (2011). Understanding cloud computing vulnerabilities. Security & privacy, IEEE, 9(2), 50-57.

Jones, T. (2012). Cloud computing and storage with OpenStack. Discover the benefits of using the open source OpenStack IaaS cloud platform.

Jones, T. (2012). Nested virtualization for the next-generation cloud. Retrieved from http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/cloud/library/cl-nestedvirtualization/

Lillard, T. V. (2010). Digital forensics for network, Internet, and cloud computing: a forensic evidence guide for moving targets and data. Syngress Publishing.

Lineage, A. W. (2011). X as a Service, Cloud Computing, and the Need for Good Judgment Retrieved from http://origin-www -ca.computer.org/csdl/mags/it/2009/05/mit2009050004.pdf

Meghanathan, N., Allam, S. R., & Moore, L. A. (2009). Tools And Techniques For Network Forensics. Retrieved from http://www.airccse.org/journal/nsa/0409s2.pdf

Mell, P., & Grance, T. (2011). The NIST definition of cloud computing (draft). NIST Special Publication 800-145. Retrieved from http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800 -145/SP800-145.pdf

Meng, S., & Liu, L. (2012). Enhanced Monitoring-as-a-Service for Effective Cloud Management.

Muniswamy-Reddy, K. K., & Seltzer, M. Provenance as First Class Cloud Data. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.eecs.harvard.edu/~kiran/pubs/cloud-ladis09.pdf

Nisbet, B. (2011). Monetizing the Cloud: XaaS Opportunities for Service Providers. Retrieved from http://www.emc.com/collateral/software/white-papers/monetizing-cloud-xaas-opportunities-service-providers.pdf

PCI Security Standards Council. Cloud Special Interest Group. (2013). PCI DSS Cloud Computing Guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/pdfs/PCI_DSS_v2_Cloud_Guidelines.pdf

Ruan, K., Carthy, J., Kechadi, T., & Crosbie, M. (2011). Cloud forensics: An overview. Advances in Digital Forensics, 7, 35-49. Retrieved from http://www.researchgate.net/publication/229021339_Cloud_forensics_An_overview/file/ 32bfe50f55377829e3.pdf

Rule 702. Testimony by Expert Witnesses. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_702

Schaffer, H. E. (2009). X as a Service, Cloud Computing, and the Need for Good Judgment. IT Professional, 4-5.

Taylor, M., Haggerty, J., Gresty, D., & Hegarty, R. (2010). Digital evidence in cloud computing systems. Computer Law & Security Review, 26(3), 304-308.

Terremark. (2013). Digital Forensics. http://www.terremark.com/services/security -services/investigative-response-forensics/digital-forensics.aspx

Toomer, L. G. D. (2011, September). FISMA compliance and cloud computing. In Proceedings of the 2011 Information Security Curriculum Development Conference (pp. 99-103). ACM.

Wang, K. (2010). Using a local search warrant to acquire evidence stored overseas via the internet. In Advances in Digital Forensics VI (pp. 37-48). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Wauters, R. (2008). Amazon ec2 now available in europe. TechCrunch. Online Publication. Retrieved from http://techcrunch.com/2008/12/10/amazon-ec2-now-available-in-europe/

Webb-Hobson, E. Digital Investigations in the Cloud.

Williams, D., Elnikety, E., Eldehiry, M., Jamjoom, H., Huang, H., & Weatherspoon, H. (2011). Unshackle the cloud. Proc. of USENIX HotCloud.